Our favorite read this weekend was an article in the Sunday New York Times Travel section about the delightful topic of what it would be like to take a vacation in Wakanda. The paper solicited suggestions from its readers, who responded with some absolutely enchanting ideas: they’d take trips to the Warrior Falls, listen to griots and poets in the marketplace, visit the rhino farm, and observe the young women training to serve in the Dora Milaje. The clear consensus was that it would be a dream journey to a peaceful, dynamic, cerebral society free of racial tension and filled with intelligent, self-governing black people who had no legacy of oppression.

A lovely dream, indeed. Which made us think: what happened to all the abortive attempts to create a real-world community like the fictional Wakanda here in America?

We’ll just say right up front that we’re a little bit obsessed with Black Panther. Yep, we’ve seen it three times. And we’re not ashamed. Each viewing showed us something different, and provoked us to think deeply about a lot of things that we hadn’t even realized we needed to wrestle with until we saw the film. So we’ve been on a bit of an emotional journey in the past few weeks. Who says art can’t transform us?

In our quest to explore the layers of meaning underlying Black Panther, including its sensational fashion, reading that New York Times article on Sunday sent us searching for books about the real-world attempts throughout history to build a community like the fabled Wakanda.

If you’re similarly curious, here’s a recommended reading list about the history of black utopias in America and their ultimate impact – and what we can learn from them that’s relevant for our lives today.

It’s a dream that any historically oppressed group of people can understand and relate to – and certainly one that we as black Americans can well understand. The dream of an independent nation – or at least a municipality – founded and governed by the formerly oppressed, and free of the brutality, violence, and everyday indignities previously experienced for generations. A Wakanda, where dignity, respect, excellence and social harmony are achievable for all members of the community.

Imagining such a place can sustain a people through the darkest of times.

That vision of a homeland — of a longed-for paradise — lives deep in the hearts of many black Americans even today, and it was there long before most of us had ever heard the name “Wakanda.” How could it be otherwise? For most, it’s the stuff of imagination and fantasy. There’s a rich cinematic history of black superheroes. There are comical and satirical takes on the idea all around us. For example, in a sketch on their now-ended cable TV show, comedians Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele took us to “Negrotown” to illustrate what life would like if black racial stereotypes and their resulting dangers simply didn’t exist. It was funny — and heartbreaking. There are hundreds of novels – satirical, sci-fi, and literary – about black planets, nations and cities. Some are inspiring, some are dispiriting, but all of them are based on an intense longing that is very real. Not so much for a new nation — but for a new America.

Of course you might say that these make-believe utopias are meaningless distractions that keep us from addressing the pressing issues at hand, but we think not. Sometimes art is a catalyst for a new reality. As one commentator noted: worlds must be dreamed before they can be made.

For a select few leaders throughout history, the creation of a self-governing, stand-alone black society founded by formerly oppressed people has been more than a daydream or a prayer. It’s been their life’s mission to make such a place real. Who were they, and what did they create? And what happened to those dreamed-of Wakandas?

According to Johns Hopkins historian Nathan Connolly, the establishment of self-determined black communities began sometime around 1512 in the mountains of Santo Domingo. Africans in the Americas broke away from slavery to form their own societies with indigenous island people. They did it again in Dutch Surinam and British Jamaica.

Subsequently, in America, there were numerous attempts to create self-sustaining, black-run communities – or so-called “black towns.” In 1908, Allensworth, California was established as a thriving farm community for former slaves. More recently, in the 1970s, Soul City was a standalone community envisioned by civil rights activist Floyd McKissick and funded by President Nixon (of all people). We couldn’t find books about a number of these cities, although we did find a research paper about Soul City and articles in the Washington Post and the Atlanta Black Star about the history of black towns (there are many more than you may have realized).

We did, however, find 9 books that provide a fascinating and sobering look into the real-world attempts to create a Wakanda here on Earth, and what happened next. From the slave revolt that led to the establishment of Haiti, to the black utopian communities built in America before and after the Civil War, to Liberia — an African nation governed for over 100 years by freed American slaves and their descendants – through Reconstruction and to the present day, the rich history and dashed dreams of these black American utopias will make you see a number of things in a new light. Dive into any one of these for a provocative and poignant view of what happens when the dream becomes reality, even for just a short moment in time.

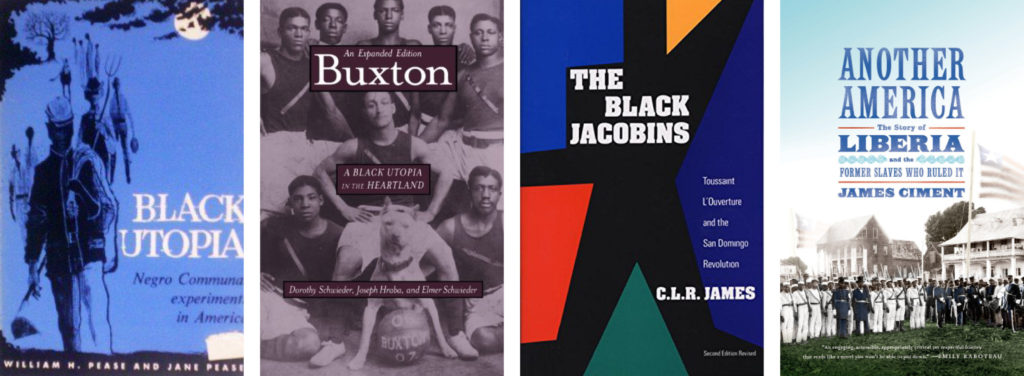

Black Utopia: Negro Communal Experiments in America by William H. Pease and Jane Pease. In the years before the Civil War, a number of communities were founded by free African Americans, with the aim of establishing vocational and academic training and political and economic independence. This book tells the stories of these utopian experiments in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, southwestern Ontario, and elsewhere, including Frances Wright’s Nashoba, the Port Royal settlement in Carolina, and the Canadian communities founded by William King, Hiram Wilson, and Josiah Henson.

Buxton: A Black Utopia in the Heartland by Dorothy Schweider, Joseph Hraba and Elmer Schwieder. From 1900 until the early 1920s, an unusual community existed in America’s heartland. It was the largest unincorporated coal-mining community in Iowa, and the majority of its 5,000 residents were African Americans – unusual for a state which was over 90% Caucasian. The authors are current and former professors at Iowa State University, and they provide a thoughtful and detailed portrait of this seminal black community.

Black Jacobins by C. L. R. James is the historian’s definitive account of the Haitian Revolution, which was driven by the fierce desire to create a black-led society. The massive 1791 slave uprising in Saint-Domingue was the start of the creation of modern-day Haiti. When the armed conflict ended in 1804, the hopes for life in a free black nation were boundless, and gave hope to slave communities across the Americas.

Set the World on Fire by Keisha N. Blain examines how black women engaged in nationalist movements from the early twentieth century to the 1960s. It tells the little-known stories of women like Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, who in 1932 spoke to a crowd of black Chicagoans, rallying their support for emigration to West Africa. And Celia Jane Allen, who traveled to Jim Crow Mississippi in 1937 to organize rural black workers around Black Nationalist causes. In Chicago, Harlem, and the Mississippi Delta, from Britain to Jamaica, the women profiled in this history built alliances with people of color around the globe, agitating for the rights and liberation of black people in the United States and across the African diaspora. As pragmatic activists, they employed multiple protest strategies and tactics, combined numerous religious and political ideologies, and forged unlikely alliances in their struggles for freedom.

Another America: The Story of Liberia and the Former Slaves Who Ruled It by James Ciment is a retelling of the the sad tale of Liberian history. In 1820, a group of about eighty African Americans reversed the course of history and sailed back to Africa, to a place they would name after liberty itself. They went under the banner of the American Colonization Society, a white philanthropic organization with a dual agenda: to rid America of its blacks, and to convert Africans to Christianity. The settlers staked out a beachhead; their numbers grew as more boats arrived; and after breaking free from their white overseers, they founded Liberia―Africa’s first black republic―in 1847. Ciment reveals that the Americo-Liberians struggled to live up to their high ideals. They wrote a stirring Declaration of Independence but re-created the social order of antebellum Dixie, with themselves as the master caste. Building plantations, holding elegant soirees, and exploiting and even helping enslave the native Liberians, the persecuted became the persecutors―until a lowly native sergeant murdered their president in 1980, ending 133 years of Americo rule and plunging the nation into civil war.

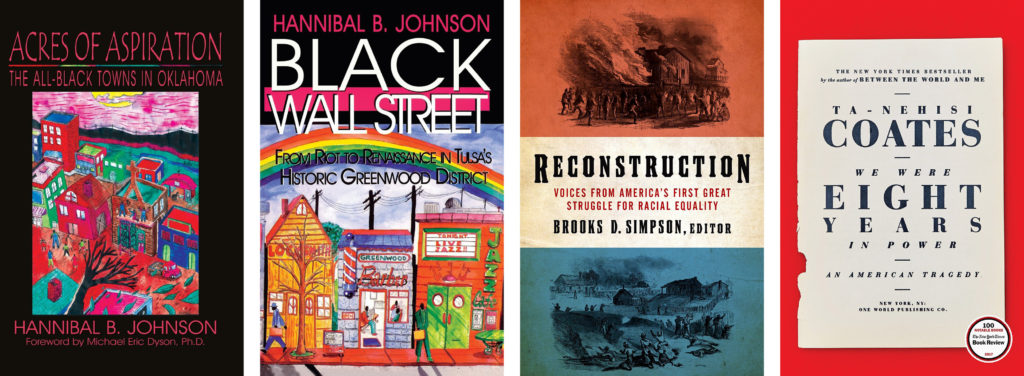

Acres of Aspiration: The All-Black Towns of Oklahoma by Hannibal B. Johnson and Clay Portis, with a foreword by Michael Dyson. Seeking both refuge and respect, pioneers such as Edward P. McCabe championed the idea of Oklahoma as an all-black state. And all-black towns proliferated there. Some sixty of them bear witness to the deep creativity and incredible human spirit of the people who built them.

Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District by Hannibal B. Johnson is the author’s second entry about the history of all-black communities in Oklahoma. Early in the twentieth century, the “Greenwood District” of Tulsa became a nationally renowned entrepreneurial center. Frequently referred to as “The Black Wall Street of America,” it attracted residents from all over the country. The community prospered in its early days. But fear and jealousy swelled in the greater Tulsa community, and the alleged assault of a white woman by a black man triggered unprecedented civil unrest. The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 destroyed the thriving district – it burned to the ground – and hundreds died or were injured. Subsequent attempts to rebuild have had mixed success, and efforts continue to restore the historic neighborhood.

Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality edited by Brooks D. Simpson is a Library of America anthology of more than 100 letters, diary entries, interviews, petitions, testimonies, and newspaper and magazine articles written during Reconstruction. With entries authored by well-known figures–Frederick Douglass, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Andrew Johnson, Thaddeus Stevens, Ulysses S. Grant, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mark Twain, Albion Tourgée–as well as by dozens of ordinary people, this is an immersive way to hear the stories of the Reconstruction era – the first real attempt to make America itself a racial utopia.

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy by Ta-Nehisi Coates. “We were eight years in power” was the lament of Reconstruction-era black politicians as the American experiment in multiracial democracy ended with the return of white supremacist rule in the South. In this collection of essays, Coates explores the tragic echoes of that history in our own time: the unprecedented election of a black president followed by a vicious backlash that fueled the election of the man he argues is America’s “first white president.”

The legacy of anti-colonial struggle and age-old visions of black self-determination remain alive and unresolved, and the deep resonance of the film Black Panther is at least partially due to its portrayal of that dreamed-of black utopia. We can’t speak for anyone other than ourselves – for us, the dream is not of establishing some new land that is isolated from the rest of the world. The dream is moving the country we already live in closer to that utopia that we carry around in our hearts. One movie may not change the world. But who knows where the unleashed energy and optimism that Black Panther has engendered may lead? “I have been to Wakanda,” one enthusiastic film reviewer explained. “And I may never recover.” Let’s hope none of us do.

Join our community

For access to insider ideas and information on the world of luxury, sign up for our Dandelion Chandelier newsletter. And see luxury in a new light.